In the spirit of reconciliation, strategic communicators need to take the time to understand what is being asked of them in this ongoing process. Reconciliation has elements of truth, justice, forgiveness, healing, restitution, and love. Supporting reconciliation efforts means working to overcome the division and inequality between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Collective efforts from all peoples are necessary to revitalize the relationship so kudos to your personal reconciliation act just by reading this blog post!

Many people do not know the full impact of Indian Residential Schools (or the many other damaging colonial practices) and how it continues to be felt throughout generations and contribute to social problems. This guide isn’t intended to outline the history of injustices in Canada like residential schools, but to provide a guide based on best practices when mass communicating with Indigenous audiences.

This demographic is not diminishing. Indigenous youth are the fastest growing segment of the Canadian population and more than 350,000 will come of age by 2026. This means your 18+ audience demographic is increasing in cultural diversity and you need to know how to reach all Indigenous peoples effectively.

Key barriers Indigenous peoples face when accessing information

Systemic barriers and discrimination facing Indigenous peoples largely stem from the Indian Act. Be sure to read the book 21 Things You May Not Know About The Indian Act, if you want to know the intent and extent of the Act and how it contributed to these key barriers today.

Even at higher numeracy and literacy skill levels than their elders, the emerging Indigenous population has a significantly lower probability of employment, inadequate housing and overall poorer health. Amongst the endless cultural genocide issues that derived from the colonial practices of the Indian Act, Indigenous peoples have higher levels of incarceration, suicide, and a plethora of other societal issues. Predominately residing on reserves, the on-reserve housing situations vary from community to community. While some communities do have an adequate supply of good quality homes, that is not the norm. This means that things like internet connectivity, access to TV/radio and other means of mass communication can be very limited in some areas of Canada.

Key principles of an Indigenous-focused communication strategy

When executing a communications strategy that includes marginalized groups of people, there will always be certain nuances that are overlooked. Incompatibilities of social classes and deep-rooted social class issues that are not widely documented for analysis are predominate issues for strategic communicators. As strategic communicators, we can only do our best to make informed decisions about communicating with Indigenous peoples and consult with cultural advisors and/or Elder Knowledge Keepers along the way.

Educate yourself on the current state of Indigenous peoples in Canada

First things first, you need to thoroughly comprehend the issues plaguing Indigenous peoples. Only by understanding the historical policies that contributed to the cultural genocide and intergenerational trauma of Indigenous peoples can you begin mass communication.

As strategic communicators, it is our role to research and understand our audiences to provide insights that will contribute to the overall communications strategy. With approximately 1 in 10 Indigenous peoples in Canada living in Saskatchewan, this demographic should be considered in all strategies. According to Statistics Canada, over half (54%) of Indigenous peoples in Saskatchewan were under the age of 25, compared with 30% of the non-Aboriginal population. This demographic is emerging and it’s our responsibility to be well versed in their history.

Over the past decade there has been significant progress in the formal acknowledgment of the past harms and their effects on Indigenous peoples. The following reports are critical to understanding your Indigenous audience and the collective issues they face:

UN Declaration of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) provides us with a road map to advance lasting reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. The individual and collective rights that were mutually agreed upon dictate the survival, dignity and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples worldwide. Canada is currently working on implementing the declaration – translating it into their own social, historical, political and legal context.

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions 94 Calls to Action

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was formed as a means of reckoning with the devastating legacy of forced assimilation and abuse left by the residential school system. The Commission heard stories from thousands of residential school survivors and in June 2015. The commission released a a report based on those hearings that outline the 94 Calls to Action. The Calls to Action are broad and aim to improve access to health care, education, language and culture preservation, child welfare services, and justice.

Final Report: MMIWG Inquiry

The National Inquiry’s Final Report reveals that persistent and deliberate human and Indigenous rights violations and abuses are the root cause behind Canada’s staggering rates of violence against Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people. The Final Report is comprised of the truths of more than 2,380 family members, survivors of violence, experts and Knowledge Keepers shared over two years of cross-country public hearings and evidence gathering. It delivers 231 individual Calls for Justice directed at governments, institutions, social service providers, industries and all Canadians.

Understand and differentiate the nuances between First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples

Terminology related to Indigenous peoples can be difficult to navigate. A term that might be acceptable to some might be offensive to others. You may think that using the word “Indigenous” or “Aboriginal” will mitigate those concerns but there are nuances that the term does not cover. Understanding the different cultural aspects of each identity will allow you to genuinely connect with your audience.

Indigenous vs. Aboriginal or “Umbrella” Terminology

Let’s dive into umbrella terminology first. Originally, The Constitution Act used the term “Aboriginal” to refer to all First Nations (both status and non-status), Metis and Inuit people. The term Aboriginal has been widely replaced by “Indigenous,” although Aboriginal is not considered derogatory and is frequently used. The term Indigenous is also an umbrella term that refers to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

First Nations

Now that we understand how umbrella terminology is used, it is also important to differentiate between the types of Indigenous peoples. Originating from the Indian Act, First Nations people have been referred to as “Native” or “Indian” and some First Nations may still refer to themselves with these terms. You should refrain from using this terminology if you are not First Nations. There are multiple First Nations identities with significant diversity between each. In Saskatchewan for example, First Nations identities mainly consist of Dene, Cree Saulteaux, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakoda with different languages and dialects among all. Many First Nations people will identify themselves as their specific identity. For example, instead of saying, “I am First Nations,” they would instead say, “I am Cree.”

Metis

The Métis Nation of Saskatchewan defines Métis as “a person, who self identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation Ancestry and is accepted by the Métis Nation.” Every descendant of a Métis person is also Métis, and the First Nations blood quantum is not used to describe or validate a person’s Métis identity.

Inuit

Inuit people primarily live in the Arctic homeland, Inuit Nunangat. Inuit is the plural term, which means “people,” used to describe Inuk (singular) persons. The majority of Inuit live in 51 communities spread across Inuit Nunangat, encompassing 35 percent of Canada’s landmass and 50 percent of its coastline. Inuit people make up approximately 4% of the Indigenous population in Canada and are often absent from policies relevant to First Nations people. They should be differentiated from First Nations peoples as they have vastly different issues in the communities of the north.

Use “everyday” level of English when communicating with Indigenous peoples and translate to Indigenous languages where possible and relevant

It’s important to note that historically, through colonial practices like residential schools, it was illegal for Indigenous peoples to communicate in their native language. They were forced to learn English and often physically and mentally abused if they spoke their native tongue. Students returning from residential schools found it difficult to communicate with their Elder Knowledge Keepers or family members and the languages were nearly eradicated. This is why is it critical to consider how you will communicate your message to an Indigenous audience. Not only to increase the overall reach and influence of your message, but to support ongoing reconciliation efforts related to the rebuilding of Indigenous languages.

It’s also important to consider who your target audience is. Are you communicating to a broader Indigenous population (16+) where the majority have been educated in English? Or is your audience skewing older (55+) where Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers may have very limited education in English and difficulties understanding the most basic English phrases.

When referring to this “everyday” level of English, it can be understood as a basic, conversational level of communication and adequate for day-to-day interactions/living. Indigenous peoples with this level of proficiency tend to have limited vocabulary and grammar but can understand both spoken and written English to some degree. They may have trouble understanding more complex words and phrases so avoiding copy that is overly expressive will help the broadest number of Indigenous peoples understand. Developing communication with this “everyday” level of English top of mind ensures that those who have been deeply affected by intergenerational trauma and colonial practices are able to understand and be influenced by your message. In instances where your audience includes an older generation, it may be best to translate your messages into the native language of the region. Seek out a cultural advisor who is fluent in the language to assist and do not use online translation systems.

Use multiple channels of communication to reach Indigenous peoples

Many Indigenous peoples are not urban Indigenous, they live on reserves where media placements aren’t as accessible. A simple solution might come to mind – target them through online/social platforms using geo-targeted tactics. Unfortunately, this “digital first” marketing strategy does not work when a subset of your audience does not have internet access. This is not true for all reserves, and many reserves have adequate connectivity, but we are striving for equality with this communications guide. If you want all Indigenous people to have a chance to see your message, you need to think holistically about how to reach the masses. It also becomes complicated when you integrate traditional tactics to your strategy. A lack of permanent housing or vehicles can limit access to traditional mediums like TV/radio so consider out-of-home (billboards, bathroom posters, band offices) placements in areas where Indigenous populations reside. So, all in all, there is no one-fits-all strategy to reach Indigenous peoples. Research your audience, find out what their connectivity levels are in the communities, and utilize multiple placement strategies to ensure equal representation.

Support Indigenous media organizations when it fits your strategy

Understandably, you will need to choose media placement strategies based on information preferences and demographic profile. Mainstream media is a necessary medium to some strategies, but where possible and relevant show your support to Indigenous-owned media organizations. Not only will you reach an engaged Indigenous audience, but your media dollars are also directly supporting Indigenous organizations. Indigenous media is growing and importantly creating employment for others so supporting these businesses is a critical aspect of reconciliation.

Be an active provider of information relevant to Indigenous peoples

There is a common misconception that If people wanted help, they would ask for it. Or at the very least take the appropriate steps (known to many as Google Search) to find out more information. You cannot presume that Indigenous peoples seek out information relating to your topic, no matter how relevant it is to them. They may not know how to look for or where to access it due to key barriers like locational issues and lack of connectivity discussed earlier. By providing information proactively and not assuming that the target audience will seek out information on their own, without being notified to do so, you have a better chance at success.

Resources for your next Indigenous land acknowledgment in Saskatchewan

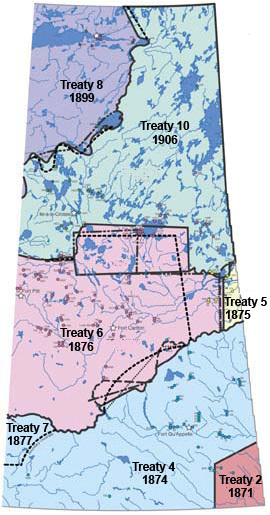

Use the tools below and fill in the blank for your next land acknowledgment using the map and insights.

“(Insert location/event) is located on Treaty (Insert Treaty) Territory—the ancestral lands of the (Insert corresponding identities). We acknowledge the harms of the past and are committed to moving forward in the spirit of reconciliation and gratitude—respecting and honouring the treaties that were made on all territories.”

TREATY 2: Cree, Saulteaux, Stoney, Nakoda, Dakota and homeland of the Métis

TREATY 4: Cree, Saulteaux, Dakota, Nakoda, Lakota, and homeland of the Métis

TREATY 5: Cree, Saulteaux, and homeland of the Métis

TREATY 6: Cree, Saulteaux, Stoney, Nakoda, Dakota, and homeland of the Métis

TREATY 7: Blackfoot Confederacy and homeland of the Métis

TREATY 8: Dene, and homeland of the Métis

TREATY 10: Cree, Dene, and homeland of the Métis

Author Bio:

I am a proud member of Nunatukavut, Inuit and hail from Nanasivik, Nunavut. This is my thoughtful perspective on communicating with Indigenous audiences based on first-hand experience. I spent years travelling across the Saskatchewan, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut creating space for Indigenous storytelling with the CBC. I’ve had the privilege of working with Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council (on behalf of their 11 member First Nations) to better understand First Nations people in Saskatchewan and all Indigenous consultation resource centres across Canada.